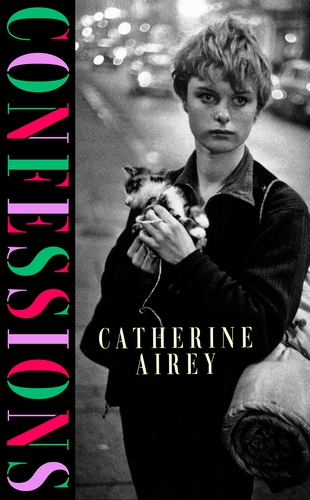

Confessions by Catherine Airey: A multigenerational story about secrets and belonging

By Paula Dennan, Deputy News Editor

Catherine Airey’s debut novel opens with intrigue as Cora Brady tells us that 'Two days after she disappeared, most of my mother’s body washed up in Flushing Creek.' This revelation is followed up with, 'Almost exactly seven years later, my father jumped from the 104th floor of the World Trade Center, North Tower.' It is September 11th, 2001, and 16-year-old Cora should be in school. Instead, she is home waiting for her boyfriend. When he is late, she drops an acid tab alone. It is in this state that Cora learns her father, Michael, and almost all of his colleagues at Cantor Fitzgerald are missing, presumed to have died.

In quick succession, Cora learns that she is the beneficiary of her father’s life insurance policy and that she has an aunt in Ireland. Róisín, her mother Máire’s younger sister, is now her legal guardian. As Cora travels to Burtonport in County Donegal, the novel takes the first of many jumps in time, spanning three generations of the family from the 1970s to 2023.

Róisín narrates much of the 1970s section set in Burtonport. Róisín’s relationship with Máire and their neighbour, Michael, a mixed-race Black boy who left Belfast with his mother when he was ten, takes centre stage. Burtonport’s old school house becomes its own character. When members of the Atlantis Primal Therapy Commune move in, it becomes known as the Screamers’ house. The Screamers’ search for an artist-in-residence sets in motion the chain of events that leads Máire to a New York art school.

Once in New York, Máire discovers that the course is not what she expected. As Máire tries to make a life for herself away from Róisín and Michael, she relies on people who do not always have her best interests in mind. All the while, her actions and behaviour have become increasingly erratic.

From here, the narrative switches back and forth between Róisín and Máire. As we move into the 1980s, Máire appears to have cut herself off from home. Róisín and Michael must figure out their relationship without Máire as its focal point. When Michael eventually follows Máire to New York, Róisín is left to build a life for herself.

Airey uses numerous narrative styles throughout Confessions, including diary entries, letters, and fiction. Máire’s sections are told in the second person, placing the reader inside Máire’s head as her life unravels. The second-person narration also lends the story a detached quality, mirroring Máire’s struggle with mental illness. I was reminded of Gender Trouble by Madeline Docherty, which uses second-person narration to portray the protagonist’s dissociated state.

The central framing device for Confessions is a text-based choose-your-own-adventure video game called Scream School. The scripts for Scream School are interspersed throughout the novel, their significance becoming more apparent as the story unfolds.

The next significant jump happens when we are introduced to Cora’s daughter, Lyca, in the 2010s. Still living in Burtonport, Lyca discovers the letters that bring Michael’s narrative to the fore. As she unearths things about her grandparents that even her mother does not know, Lyca grapples with whether to reveal their secrets to Cora. How can she, when there is already so much about her mother’s life that Lyca does not understand?

There is a case to be made that the reader does not get the complete details about Cora’s job or role during the Repeal the Eighth referendum because we learn about it from Lyca, which is indicative of their often strained relationship. This makes sense to me on a storytelling level. However, as a reader, I felt cheated that we hadn’t witnessed Cora’s growth since moving to Burtonport.

I felt similarly about an aspect of Róisín’s story that significantly shaped her life in later years. By taking the action off the page, Confessions references the social issues that have changed Ireland over the last decade without truly confronting them. This would not be a problem, except that we are repeatedly told how these issues affected Róisín and Cora. Showing us would have had more of an emotional impact.

Nevertheless, this multigenerational story about secrets and belonging is a compelling and intricate debut that kept me engaged as a reader, even when I wanted more on the page. Confessions has been compared to Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch, given its intricacy. The video game element reminded me of Gabrielle Zevin's Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. While the expansive timeline made me think of Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides. Confessions sits at the intersection of commercial and literary fiction, giving it a broad appeal to readers who enjoy the interiority of character studies and propulsive storytelling. Catherine Airey is undoubtedly a writer to watch, yet there are times when Confessions contains one too many coincidences for this reader to be able to suspend her disbelief entirely.

Confessions by Catherine Airey is published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House.