Ireland’s Housing Crisis Deemed Perfect Fit for Far-Right’s Anti-Immigration Narrative

By News Editor Marc Galdes

‘Housing and homelessness crisis is a key catalyst for anti-immigrant sentiment, and is therefore a serious barrier to integration’ says the Joint Committee on Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth in a report on refugees following the Dublin riots.

The housing crisis is certainly not a new topic for our readers but who’s to blame for this?

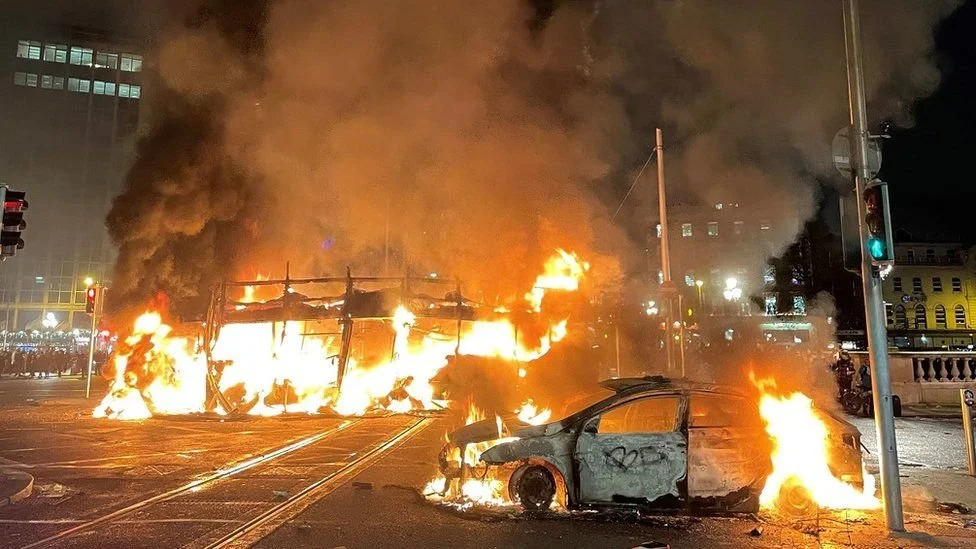

2023 Dublin Riots

The frustration surrounding the lack of housing available has caused a number of protests to take place against refugees which has strengthened the popularity of the far-right, not only in Ireland, but all throughout the EU.

The most severe retaliation by far-right protestors against migrants was the Dublin riots back in November, which erupted in response to news that an Algerian man had stabbed three children and a care assistant. The violence did not stop there, following these riots arson attacks took place at a building site for an asylum seekers centre in Rosslare, Co. Wexford, where asylum seekers were set to arrive in the coming weeks.

Nonetheless, this was not a one-off. Similar protests were previously seen in 2022.

Closer to home, hundreds gathered at the gates of St Dominic’s Centre (a historic former religious property) in Mayfield on 22 January after the Department of Integration confirmed that it was being considered as a possible accommodation to house Ukrainians. A day after the protest the Integration Department withdrew its interest in the property.

Anti-migrant protest at St Dominic’s, Cork.

During the 2020 general election, far-right candidates performed poorly overall. This means that the far-right is still considered to be a very small movement in Ireland, but there are concerns that is growing in popularity. Although small, the movement is retaliating violently.

Far-right parties such as the Irish Freedom Party and Ireland First, as well as activists such as Derek Blighe, are actively promoting these protests. The Irish Freedom Party’s website declares that the main way to solve the housing crisis would be by effectively controlling immigration. Hermann Kelly, who is from the party, has also been vocal against Ireland’s ‘reckless open borders’. The Irish Times also revealed that within Ireland First’s telegram group chat, there was overt racism, homophobia, antisemitism along with calls for violence against refugees, even though the party had formerly claimed to not be racist.

People Before Profit-Solidarity party lawmaker Mick Barry argued in the Dáil that the only way to stop social upheaval from taking place would be to solve these issues. ‘You cannot pepper spray alienation, you cannot baton charge anger at social inequality… you cannot taser the housing crisis or use water cannons to wash away a culture of toxic masculinity.’ But is that easier said than done?

What, Where, How refugees?

Both the terms asylum seeker (international protection applicant) and refugee are misused frequently throughout the media and there is much confusion surrounding where they are housed.

An asylum seeker is someone who might have fled their country due to war or conflict, but they are still waiting to be granted refugee status. Until they are granted refugee status, they are held in direct provision accommodation centres, which have been scrutinised by media for their poor living conditions. If their situation does not make them eligible to be granted refugee status, then they are repatriated. However, it is perfectly within anyone’s right, under the UN’s Declaration for Human Rights, to seek asylum: ‘Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.’

A refugee is a person who fled their country of residence, usually because of war or conflict, and now resides in a different country after being granted refugee status. Also, the country which houses the refugee has the obligation, under the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, to offer protection for the refugee.

In the case of Ukrainians fleeing the war, they are automatically being offered protection under the 2001 Temporary Protection Directive which was activated in March 2022 by the EU Council, following proposal from the EU Commission. This would include giving them access to social welfare, suitable accommodation, education, and so on. In other words, they are immediately treated like a refugee and not an asylum seeker.

Asylum seekers are housed in direct provision centres but due to the significant number of Ukrainians reaching Ireland’s shores, some Ukrainians have also entered direct provision since there is no housing available. To solve this, the Department of Integration has been seeking out community facilities, industrial buildings and hotels which could be used as emergency accommodation centres to house asylum seekers and/or Ukrainians. This has been put to action in places like Racket Hall Hotel in Roscea, Co. Tipperary (which caused several protests) and was what almost took place in St Dominic’s Centre in Mayfield.

The lack of housing for asylum seekers is so severe that on several occasions last year, asylum seekers were given tents and had no other option but to camp outside on the street as there was no space for them indoors.

Tensions rise in March 2023 as anti-racism and anti-migrant protestors clash in Cork.

Breaking Down the Narrative

Amidst the anti-migrant protests, protestors have raised concerns over the fact that asylum-seekers and Ukrainians are being given priority in social housing. Considering asylum-seekers have no legal residency, then they cannot apply for social housing.

In the case of Ukrainians, although they were given housing, back in May 2022, Housing Minister Darragh O’Brien told Newstalk that Ukrainians would not have access to social housing which is intended for people on the social housing list.

Another main issue that is raised amid the housing crisis is high rent and property prices. However, blaming refugees and asylum-seekers for this when many, as a result of conflict and/or displacement, are low-income, simply lacks grounds.

Secretary-general of Housing Europe Sorcha Edwards told Politico that allegations that the housing shortage is due to asylum seekers are simply untrue. ‘You have to have legal residency to opt for public housing in all EU states and private housing prices are not being driven by the demand of low-income foreigners.’

Another concern that has been raised by protestors is that the government is singling out emergency accommodation in places where resources are scarce. In fact, this point was also brought up in the report published by the Joint Committee on Equality and Integration. However, the Department of Integration responded to this by saying that the crisis is so severe that it is ‘not really in a position to veto particular locations.’

How is the Government Coping?

Whether this is directly impacting the rental and housing prices or not, the government is evidently struggling to keep up with the sheer number of Ukrainians arriving on Irish soil. The most recent statistics from the Central Statistics Office in October show that 96,338 Ukrainians have arrived in Ireland so far and thousands more have arrived since, which has cost the government hundreds of millions of euros to offer them protection.

Although the government has time and time again expressed its solidarity with Ukraine and offered its refugees protection, the narrative is beginning to change. Back in October, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar told the Dáil that Ireland has reached its ‘limit’ to house asylum seekers and refugees. More recently, at the beginning of the year, the Cabinet signed off on changes to support Ukrainians, which would limit the amount of time new arrivals from Ukraine can reside at State-provided accommodation to 90 days, whilst also drastically cutting their financial support. Also, speaking in the Dáil recently, Social Protection Minister Heather Humphreys said that there is a possibility that in the future social welfare cuts will apply to all Ukrainians under protection and not just new arrivals.

When talking to reporters in Galway, Varadkar added that the situation is no different with around 5,000 asylum-seekers who have been granted international protection (refugees). They are still residing in the direct provision accommodation centres as there is no space for them anywhere else.

In Brussels, politicians have been outspoken that this is as much a European problem as it is a national problem. In a story released by Politico, the European Commissioner for Jobs and Social Rights Nicolas Schmit said, ‘Europe should be involved in solving this housing crisis.’ Others, like Edwards, said that this issue can be tackled by bloc institutions and implementing an EU housing task force which would discuss policies to solve this crisis.

With an MEP election right around the corner and the national elections next year, housing most certainly will be the hottest topic on the agenda.

Although the government has offered its support to Ukrainians and asylum seekers so far, it seems like it will have to lessen the support as it cannot keep up with the large numbers. Nevertheless, it does not seem like protests charged by an anti-immigration narrative will cease to exist, but only elections will show whether the far-right has actually gained any significant popularity in the polls. We can only hope that the violence doesn’t escalate any further.

2023 Dublin Riots