Ireland’s Referenda Results: A Failure to Understand the Public?

By News Editor David Patrick Twomey

Ireland’s modern constitutional reforms have helped push the country from its traditionally anachronistic view and influence of society into one of Europe’s most liberal cultures and legal systems. For the generation who have been raised in twenty-first century Ireland, it can be easy to not comprehend the speed of the country’s departure from a Catholic principled constitution, and these changes have been primarily driven by the public vote. In 1995, the constitutional ban on divorce was lifted in a closely contested referendum. In the last two decades, Ireland has voted to amend the constitution to repeal the 8th Amendment on abortion rights as well as legalising gay marriage. This rapid social change, driven by the public vote, has placed Ireland as a highly progressive society after an intrinsic history of conservatism.

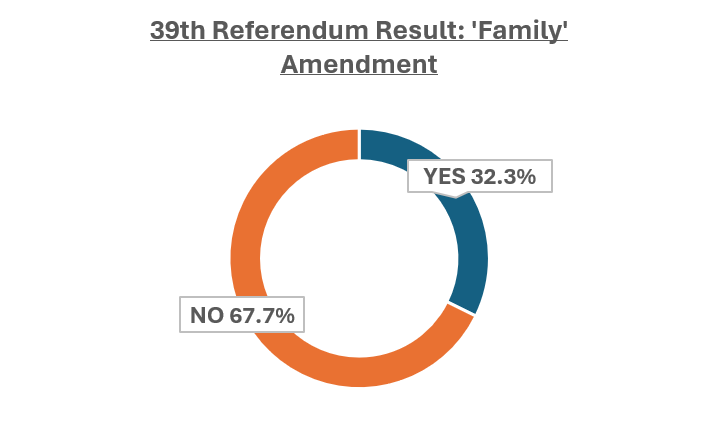

However, Ireland’s recent referenda (The 39th and 40th Amendments to the Constitution), proposing alterations in the constitutional definition of family and women’s roles in care, were definitively defeated in the public vote with record referendum margins for the ‘care’ amendment proposal. Although these were symbiotically posed as a further progressive step for society, the utterly convincing response from the public has been influenced by varying factors in the amendment proposal and surrounding issues rather than merely a regression into the erstwhile conservatism of the nation.

Source: RTÉ

What were the Proposed Amendments?

Although these votes were separate, both pertained to the area of family in Ireland. The 39th Amendment proposed was in Article 41.1.1, changing from:

“The State recognises the Family as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society, and as a moral institution possessing inalienable and imprescriptible rights, antecedent and superior to all positive law”

To:

“The State recognises the Family, whether founded on marriage or on other durable relationships, as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society, and as a moral institution possessing inalienable and imprescriptible rights, antecedent and superior to all positive law.”

It also amended Article 41.3.1 from:

“The State pledges itself to guard with special care the institution of Marriage, on which the Family is founded, and to protect it against attack.”

To:

“The State pledges itself to guard with special care the institution of Marriage, and to protect it against attack.”

This referendum asked to broaden the scope of definition for family to include cohabiting couples and other non-traditional family units.

The 40th Amendment in regards to care was in Article 41.2.1 and Article 41.2.2 to insert a new Article 42B.

“In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.” (Article 41.2.1)

“The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.” (Article 41.2.2)

The proposed amendment has two changes: deleting the first article above and inserting the new Article:

“The State recognises that the provision of care, by members of a family to one another by reason of the bonds that exist among them, gives to Society a support without which the common good cannot be achieved, and shall strive to support such provision.” (proposed Article 42B).

This referendum asked to change the outdated mothers’ ‘duties at the home’ which has been cited by many as sexist, recognising that all family members can provide care for other family members regardless of the gender of the person. Although two separate referenda, these changes in the constitution were put to public vote by the Government due to similarly outdated wording, both in terms of women in the home and their position in responsibility to care for family members. According to Minister for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth of Ireland Minister Roderic O’Gorman was to change the demeaning position of women in Irish life which should be changed to reflect the developed position of women in society and the workplace.

Rejection of the Amendments

These amendments were almost entirely rejected in Irish constituencies: Dún Laoghaire was the only outlier to vote Yes on either one of the proposals, voting 50.29 per cent in favour of the ‘family’ referendum. County Donegal witnessed the most decisive ‘No’ votes, with 80.2 per cent voting against the ‘family’ referendum and 84 per cent voting No on the ‘Care’ referendum. Some Dublin constituencies had very narrow No vote majorities in both cases.

This firm rejection of the government proposal on constitutional changes, was reflected on by Taoiseach Leo Varadkar;

“I think we struggled to convince people of the necessity or need for the referendum at all, let alone the detail and the wording. That’s obviously something we’re going to have to reflect on into the weeks and months ahead.”

So why did the Government ‘struggle to convince’ the people of Ireland to be in favour for this change driven by progressive positioning? There was of course a multitude of factors in this, but a number stood out as the key criticisms of the Amendments.

The No campaign argued the changes on many fronts, including that the amendments would change relatively little in reality, legal issues potentially arising with the changes, and due to the wording of changes could potentially alleviate the Government’s legal position to provide care.

Potential Avoidance of State Responsibility?

The proposed amendments by the Government are facing a developing scandal as internal files which were covered by a Freedom of Information Act suggest that the wording of the ‘care’ amendment was chosen to ‘avoid a concrete and mandatory obligation’ on the State to provide care. The rejected proposals by officials to replace the word ‘strive’ to a more concrete responsibility on the state were rejected. Ministers had insisted that the wording of the amendment had no taxation or immigration implementations, but the files releases mentioned that officials had been discussing tax issues and had legal advice stating that an increased weight would be given to non-marital family rights ‘in childcare, immigration and social welfare’ which would create uncertainty for judges in the lack of definition for family units. The initial plans for the Government to add such a definition for the new concept of family in law was dropped from referendum despite officials declaring its vital importance, the files show.

The Coalition Government (Fine Gael, Fianna Fáil, Green Party) had supported a Yes-Yes vote and had campaigned for such, as did all parties in Ireland other than Aontú, a republican, socially conservative and economically centre-left opposition. Aontú Meath West TD Peadar Tóibín argued that “The people do not trust the Government, and even the main Opposition parties seem to be detached from the people and aren’t listening to them”. Sinn Féin, who had backed a Yes-Yes vote and had promised a rerun of the referenda if it was defeated, took a U-turn after the definitive results. Perhaps a key reason for this potential lack of trust in government was the indecisive remarks regarding the State’s role in the care amendment. When asked about this, Taoiseach Varadkar responded “I don’t actually think that’s the state’s responsibility, to be honest”. After facing criticism for these comments, Varadkar argued that ‘Half of it was clipped’ and that it was taken out of context on social media. Yet these dubious responses caused enough scepticism for much of the population.

Politician and No campaigner Martin McDowell followed this position, arguing that “Government spokespersons consistently misrepresented the substance of the legal advice that they were receiving from the AG and elsewhere’’, misleading the public (Minister O’Gorman rejected this claim). On the day before the referenda, The Ditch published an article on unpublished advice from the Attorney General Rossa Fanning to Minister O’Gorman. Fanning advised that “It is difficult to predict with certainty how the Irish courts would interpret the concept of ‘other durable relationships… The courts may well address the question of what constitutes a ‘durable relationship’ on a case-by-case basis, having regard to the facts and circumstances of the particular case and the evidence before it”. However, Minister O’Gorman had said just a month previous that “The very clear legal advice we’ve received throughout from the attorney general is that these items (family, immigration and social welfare laws) will not be impacted by what we’re proposing to amend in the Constitution” in an interview with the Irish Independent.

This misguided information has faced backlash since publication; a Green Party source claimed that following the results, ‘Rod (O’Gorman) has been left out to dry by Leo (Varadkar)’. The messiness of both the aftermath and juxtaposing statements by Government in the run-up reflect a key issue; this referendum held in March rather than coinciding with European and local elections in June, which would have given the Government more time to iron out and explain the believed necessity and effect of these changes. The blame for this fast-tracked schedule has been left by many at Taoiseach Varadkar’s feet, claiming it was believed that a win would push one foot in the door for the upcoming elections. The Green Party sourced claimed that “There was only one person insisting on the timing of this – that it happened pre the local elections – and it wasn’t Roderic O’Gorman”. Varadkar has admitted that ‘There are a lot of people who got this wrong and I am certainly one of them.’ Although the fast tracking of the referendum to boost election results is merely a claim by inside sources, the convoluted messaging in the compact window for explaining the necessity of changes clearly had its effect on not convincing the public on why these amendments were truly necessary.

NGOs and the Criticism of ‘Care’ Changes

Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) played a pivotal role in the public debate in the run-up to the March 8 votes. Minister Roderic O’Gorman stated that:

“I think it has to be acknowledged that the departure from the wording of the Citizens’ Assembly meant that some of those NGOs and civil society organisations, who would have been supportive originally, didn’t feel they could support and (didn’t) feel they could campaign to the same degree.’’

NGOs which advocated Yes-Yes voting faced fierce criticism pre-referendum, with The Family Carers Ireland (FCI) having to turn off comments online de to backlash. Many No campaigners and organisations have questioned the referendum campaigns of State funded interest groups and NGOs. The Government had spent millions on various Yes campaigning groups, and issues of oversight have been raised. The McKenna ruling from the Supreme Court has banned public spending to third parties ‘for political purposes, including a referendum campaign’ but the Electoral Commission and the Standards in Public Office Commission released that they had no jurisdiction as to whether NGOs comply with the Supreme Court decision. This meant that the potential influence of State funding on NGOs’ public stance on the issue had little to no oversight.

The aforementioned FCI backlash was compounded by the NGO’s statement post-referendum that “we are disappointed that we did not manage to persuade people of the merits of the wording of Article 42B”. Michael O’Dowd, co-founder of Equality not Care, called for the resignation of FCI leadership as “Their whole objective of Family Care Ireland during the campaign was to act as surrogate for the Government. The detriment of the carers it was set up to lobby for.”

NGOs, if not having funding influences for referendum stances, at least had rhetorical influences; in January Minister O’Gorman stated that “any organisation that sees itself as progressive and as wanting to advance progressive change” would have to explain why they do not support the plans. No campaigner Senator McDowell had stipulated that this was a warning to NGOs on deciding their position.

An important reasoning as to why there was criticism of NGOs publicly supporting the change was due to the potential implications of the vague legal wording of the ‘care’ amendment. Free Legal Advice Ireland (FLAC), a human rights NGO, in a published legal analysis of the amendments stated that the ‘family’ amendment ‘will ultimately have positive policy and legal implications’ in areas such as social welfare, taxation, succession and family law. However, regarding the ‘care’ amendment, they believe ‘that the wording of the proposed ‘care’ amendment is as ineffective as the current so-called ‘women in the home’ provision. It is unlikely to provide carers, people with disabilities or older people with any new enforceable rights or to require the State to provide improved childcare, personal assistance services, supports for independent-living, respite care or supports (at home or in school) for children with disabilities.’

FLAC added that the wording portrays ‘harmful stereotypes’ for the provision of care for family members is ultimately a responsibility of the family, ‘without any guarantee of State support’. Although the Government firmly said that the ‘strive’ for care would be an express obligation for the State, many disability and care campaigners questioned if the amendment would actually give any new rights for the disabled community in court.

Chief Executive of Inclusion Ireland, an NGO representing people with intellectual disabilities and their carers, announced that the organisation could not support the new Article 42B as it was ‘nowhere near strong enough’, arguing that the ‘Government underestimated the level of anger and determination among carers and disabled people…The only way forward is to build solidarity with a firm focus on human rights.’ This question of legal impact was at the fulcrum of the No campaign. Although changing Article 41.2 to gender neutral terms was seen as a positive change, it was deemed as merely an expressive gesture of inclusion for many. FLAC stated that from a legal standpoint, the new Article 42B “does nothing to enhance, and potentially compromises” the rights of people living with disabilities as under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (UNCRPD) due to its negation of a definitive legal support from the State. This contention of ineffectiveness and perhaps detrimental change in this amendment helped it be become a unique result; the largest majority ‘No’ vote in a referendum in Irish history.

The result of this referendum lies in contrast to Ireland’s recent history of rapidly advancing progressive changes to the constitution and society which have been decided by public vote. However, this resounding defeat is not a straightforward case of another western country retracting to conservatism. Social Democrats leader Holly Cairns pre-referendum understood that many on the left wanted the Amendments to go far further in legal influence but stated that ‘we will be voting yes based on the two options that we have.’ However, the Government’s failure to listen to the attorney general, many officials, and legal and care NGOs in delivering options which did ‘go further’ allowed the discourse to question why these specific changes would be necessary to drastically improve the quality of life for many Irish.

The Yes campaign ultimately failed to define the necessity of these changes for modern Ireland, and the rising criticisms of not legal advice on definition as well as issues of NGO influence have mired the campaign. Although the argument that these parts of the constitution have become outdated were generally accepted, their unclear amendments caused more questions than answers. Ultimately, the proposed amendments can be seen as ‘a missed opportunity for the rights of women, carers, older people and people with disabilities’ (FLAC). The potential fallout or lack thereof for the fervent Yes campaign within Government is unclear so close to the decision, but the continuing publication of campaign criticism may mean that the results of the referendum are unlikely to be the end of this story. But what is abundantly clear from the Referenda’s results is that the Government’s understanding of the public zeitgeist and needs has been utterly incorrect.