The Past and Future of AI Art

By Luca Cavallo, Arts & Lit Editor

It is a common tradition among students homebound for Christmas to watch an absurd amount of movies. It is an even more common tradition to watch movies that have a Christmas-exclusive ‘vibe’, and I’m not just talking about Hallmark Christmas movies. It seems that a sense of nostalgia becomes crucial for the holiday season. We find this in classic series of films like Harry Potter, Indiana Jones, Lord of the Rings, and so on. However, this year I found myself strangely acquainted with movies connected by nothing other than history and setting: British period dramas. The Dig (2021), Gosford Park (2001), and The King’s Speech (2010) have all become favourites, but one movie has stuck with me despite the Christmas tree coming down: The Imitation Game (2014). It’s not a perfect movie, not by a long shot, but Alan Turing’s (Benedict Cumberbatch) eponymous ‘game’ fascinated me. It has been renamed the ‘Turing Test’, and is a series of questions to determine if you are a human or a machine.

The ‘Turing Test’ has become a staple in the early stages of artificial intelligence (AI) development. Questions usually involve one’s personal history, such as ‘How do you feel when you think of your childhood?’ One question that drew my eye as a literature nerd, however, was, ‘Describe why time flies like an arrow but fruit flies like a banana?’ The question intends to poke fun at a computer’s inability to comprehend expressions like idioms and similes… in the 1950s. Today, the average chatbot or AI text generator can thoroughly comprehend any piece of text. In The Imitation Game, Alan remarks that he ‘really is quite good at crossword puzzles’, and probably doubts that a machine could solve cryptic clues. In May 2023, an app called ‘The Crossword Solver AI’ was launched, which has the capability to outperform the best of crossword experts.

So, the ‘Turing Test’ may be defeated. After all, an MIT-designed computer managed to fool a judge way back in 1966. It was only a matter of time until machines managed to imitate the way humans think. It was Alan’s big question for his computer: ‘Can it think like a human?’. It seems that the final bulwark against this proposal was creativity, specifically artistic creativity. Sure, a machine can crack the code of crossword puzzles, solve them, and decipher brain-teasing clues in a matter of seconds. But can it make art? Can it create something out of nothing, as a simple expression of its being? Not yet, but I worry that it’s getting there.

For the purpose of establishing an order to the progress, or evolution, of AI’s relationship with art, I will separate the advancements in technology into 3 phases, as follows:

Phase 1: Algorithmic

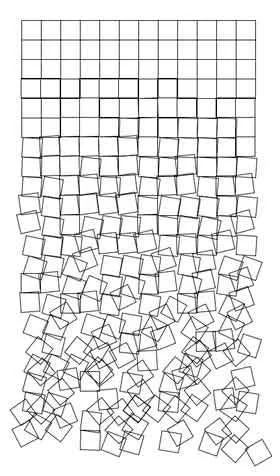

Würfel-Unordnung by Georg Nees

The first creations of artificial intelligence were unsurprisingly simple, compared to the output of the past few years in AI art. The ‘3N’ were a trio of artists from the '60s who are considered pioneers of algorithmic, or computer-generated, art. They are Frieder Nake, Georg Nees, and A. Michael Noll. Georg Nees was keen on using a machine known as a ‘plotter’ to implement his algorithm onto paper. Consider his 1968 piece, Würfel-Unordnung, where he allows the machine to take his original, ordered blocks and rework them into a new design. The algorithm is clearly endless, and the artistic process begins and ends with the human artist. But even in the 1960s, it is clear that artists were curious to give up their sense of control and allow a machine to take their algorithm, and create something new. The outcome of such early work is predictable in a way, but it cannot be denied that these artists laid the groundwork for generated art. Whether or not the evolution of AI art is a good thing for the modern age is a question that has only arisen since entering phase 2.

Phase 2: Collaborative

Harold Cohen and AARON

This is our current phase, which dates back to the 1970s. Harold Cohen is the earliest and most notable artist to incorporate AI in the creation of his work. He built the program, AARON (not an acronym), to work alongside and create art. He intended for AARON to be a ‘human-like’ program that could ‘exhibit cognitive capabilities quite like the ones we use ourselves to make and to understand images.’ For this reason, AARON has since been called the art equivalent of a ‘Turing Test’. AARON was the first step in having a computer ‘think like a human’ on a creative level. Of course, the program underwent major changes throughout its lifetime (if computers can have lives?). For example, Cohen had to change its code almost entirely in the 1990s to try and help AARON understand the complexity of colour. Before then, AARON had generated black-and-white shapes and figures, and Cohen had then painted over them. AARON was not open-source, and so when Cohen passed in 2016, AARON essentially died with him. In this way, the human and the machine could almost be considered partners.

AARON cannot create original images. It does not work independently, hence its shutdown after Harold Cohen’s death. The program also seems to have developed typical styles and repeated patterns. Remarkably, it achieved the creation of human figures and plants with colour coordination, but perhaps this was the limit to its otherwise impressive feats. By comparing the preliminary achievements of the ‘3N’ with the adaptive nature of AARON’s later production, we may begin to see what an actual understanding of artistic value in the work of artificial intelligence could be. Of course, this understanding couldn’t have been achieved without human programming, but there lies the concern that our groundwork for AI art is just a springboard for the technology to leap from.

Phase 3: Independent

Otherwise known as our dependence on the machine, this is a phase we have only just realised in the past few years. AI art has become increasingly popular on social media platforms. Modern image generators may only require simple prompts to create entire pieces, as opposed to the tedious process of generating images from algorithms 50 years ago. While many of the AI art creators on platforms like TikTok and Instagram could simply be hobbyists, not artists pursuing careers with their craft, the traction for AI art has increased in mainstream media, too. The fear of artists losing their jobs to AI is becoming a reality. In 2023, Netflix released an anime short titled The Dog & The Boy that admittedly featured AI art for its background scenery. The short received major backlash for this very reason. Netflix Japan claimed they had turned to AI due to a labour shortage, but they haven’t given any proof to this claim. 2023 also saw the Writer’s Guild of America strike (from May 2 to September 27). A serious concern among the writers on strike was that AI generators such as ChatGPT would be advanced to replace their creative output, devaluing their labour exponentially. ‘The worry,’ said John August, ‘is that down the road you can see some producer or executive trying to use one of these tools to do a job that a writer really needs to be doing.’

A reliance on AI for art seriously concerns the creative community. But although AI unfortunately improves in artistic quality over time, it cannot yet create anything truly original. In a way, it is the same as a 1960s computer taking the ‘Turing Test'; it can only imitate. The line between ‘human’ and ‘machine’ is becoming blurred, but this is only a surface level. If anything, independent AI art will only prove to humanity that we value pure human-made art above anything a computer can replicate. It isn’t likely that AI will lose its popularity any time soon, but neither will the work of the real writers, or the genuine artists.